The Death Trap: Going Underground in Jasper's Hidden Cave

How a cave specialist and a paleontologist are piecing together Alberta’s post-glacial fossil record by exploring mountain caves.

Story by Niki Wilson.

Highline Magazine, Summer 2013 edition.

Rappelling down a 30-metre vertical shaft into a cave in the Rocky Mountains was a first for paleontologist Dr. Chris Jass. “It was nerve-racking,” says Jass, who would have been more anxious had he not teamed up with Greg Horne, a cave specialist with Parks Canada. Jass gratefully describes Horne as a “safety first” kind of guy when, in 2009, the two were investigating a cave in eastern Jasper National Park.

Too intrigued by the cave’s suspected contents to let his fear get the better of him, Jass slowly lowered himself until he stood by Horne on the cave floor. As his eyes adjusted to the dim light, he was rewarded when the dusty beams of their headlamps revealed chunks of bones and fossil-filled rubble scattered on the cave floor. Jass had gotten what he had come for.

BEHIND THE SCENES

The story actually begins 12 years earlier when Horne first visited a similar cave, also in the eastern part of Jasper National Park. Colleagues at Alberta Fish and Wildlife suspected this cave was one of a few known little brown bat hibernacula in the province, and Horne was sent to investigate. Once inside, Horne quickly established the truth of it – little brown bats huddled in furry clumps along limestone walls, deep in hibernation to conserve energy in the winter months.

While confirmation of the bat hibernacula was important for regional bat conservation, Horne was more captivated by what generations of bats had left behind – a yellowed carpet of bat bones and skulls glowing in the light of his headlamp, accumulated over hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

And there weren’t just bat bones. As Horne carefully moved around the cave, he saw the skulls and jawbones of large carnivores, perhaps bear or wolverine. These animals had presumably fallen to their deaths at the steep entrance or “vertical trap” of the cave. Horne rightly suspected these bones could have significant paleontological importance. He logged the experience in his memory bank, and there it sat for over a decade.

In 2008, Jass, then a new paleontologist at the Royal Alberta Museum, contacted the Alberta Speleological Society, an organization promoting responsible, safe and environmentally sensitive cave exploration. Horne, an accomplished caver with experience in caves from New Zealand to Nahanni, had been a member for 18 years.

Jass was keen to connect with anyone who had sited bones in Alberta’s mountain caves. He had recently moved to Edmonton from Texas, after having spent his PhD identifying 150,000 year-old fossils from a cave in Nevada, and examining patterns of change over time in mammal fauna in the U.S. Great Basin between the Rockies and Sierra Nevada.

GETTING DOWN AND DIRTY

Now in Alberta, he wondered what bones and fossils preserved in caves could tell us about biological patterns after the last ice age. Did communities come back all at once, or as individual species? Were they the same species as before? Although fossil records existed for large mammals in parts of central Alberta, the post-glacial record in the Canadian Rocky Mountains was virtually non-existent.

Horne contacted Jass to let him know about the caves in Jasper National Park. He was keen to take Jass into the caves for a look, and a year later, after a significant rappel down a narrow shaft, Jass and Horne stood side-by-side in their first joint cave expedition.

They noted the sediment of the cave floor appeared to have been disturbed from previous human activity and possibly water drainage. Like a knife through a layer cake, some of this disturbance had exposed thousands of years of intact sediment strata. This piqued Jass’ interest because it meant the deposits in each layer would be the same age, providing enough material for radiocarbon dating. The two decided to return later for a proper dig; in the meantime, they made use of their research permit to collect a sample of the loose rubble for analysis in Jass’ Edmonton lab.

UNEARTHING SECRETS

Under a microscope, Jass found tiny fragments of bones. One was the jawbone of a tiny shrew. He also found surprising numbers of tiny land snail shells, 1-2 mm in size, patterned with beautiful spirals Jass could only detect at magnification. “I didn’t expect so many of the snails, given the nature and structure of the cave,” says Jass, adding that we don’t have a great understanding of land snail fauna “because few people work on them, and they’re so small.” The fact that the entrance of the cave sits in a bowl-shaped depression may account for the large numbers. “Snails are likely washed in from the surrounding landscape,” Jass explains.

Jass and Horne later returned to the cave to conduct a “terminal dig,” in which fossils and bone were properly retrieved from the intact sediment layers. Jass identified the bones of salamanders, amphibians, snakes and even fish, perhaps discarded by birds of prey.

Charcoal from the same sediment layers provided a proxy date for the bones, indicating that most were between 1,700 and 2,700 years old. The quantity of charcoal indicated that a massive fire had once ripped through the area. “We’re talking a fire that would have incinerated part of the park,” says Horne.

The team was also surprised at the results of radiocarbon dating of a black bear pelvis found in the cave. At 6,000 years old, it was 3,000 years older than anything previously found in the rest of the cave.

These findings were a treasure trove, filling a major gap in the fossil record that had been previously missing from the post-glacial record in this area. Their discovery indicated that animals had returned to the mountains at least 6,000 years before present (BP).

The excitement grew when, along with Dave Critchley of the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology, the team visited a high elevation cave that has sub-zero temperatures year-round. There the team collected hardened woodrat dung that was eventually radiocarbon dated to 9,600 years BP, a time not long after the glaciers receded.

When he discovered the date, Jass was staggered. He double-checked the results. “That’s a fairly early date relative to what we currently know,” says Jass. “If woodrats were back, that probably means a lot of other rodents were back too. That gives us a minimum date for when small mammals reoccupied high elevations of the Canadian Rockies.”

These discoveries were just the beginning for Jass, who is still carefully sifting through more of the collected sediments. “It’s exciting because of the lack of data in the mountain area. I wouldn’t be surprised to find something older.”

These unraveled cave mysteries tell us that the suite of wildlife seen in Jasper National Park today is much the same as it has been for the past 6,000 years. Jass’ continued work may soon tell us which species re-emerged first, and when they arrived. Along with data from explorations in Rat’s Nest Cave near Canmore, these geological death traps are providing a broader view of post-glacial re-colonization in the Rockies. Although not always as exhilarating as dangling from ropes into caves, for Jass and Horne it’s exciting enough to solve these mysteries cave by cave, and bone by bone.

*Bonus: The making of the Death Trap Diorama

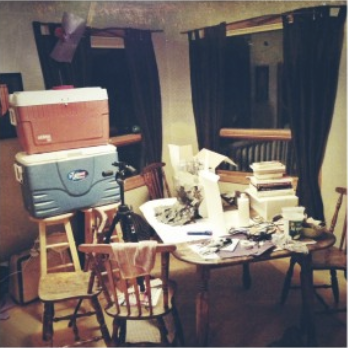

Highline’s Kristy, Camara and Brita brought the diorama back this issue with their constructed illustration for Niki Wilson’s piece, Death Trap, that featured the recent discovery of a prehistoric bone-filled cave in Jasper National Park.

Curious how they did it? Here’s some insight into their (ridiculously time-consuming) design and construction process and some tips on how to make something like this yourself.

WHAT YOU’LL NEED:

Always keep a tidy workspace.

2 x 24-pack boxes of your beer of choice. You will need both: the boxes and the beer.

children’s plasticine

leftover paints and brushes from another project you started in the ’90s

hot glue gun

construction paper

a ruler

scissors

Google

two iPhones with the FlashLight App

a pen-light

a bit of free time (ie. at least a spare forty-hour work week)

HOW TO GET ‘ER DONE:

***Before getting started, ask a busy friend to spend hours designing and executing a highly technical paper cutting illustration that you will later unceremoniously “repurpose” beyond recognition throughout the assembly of the final diorama. (see point #9)

1.) Using one of the beer boxes and glue gun, assemble your background and foundation.

2.) With your ruler and the other beer box, measure and cut out 1700 identical right triangles.

3.) Glue 1700 triangles onto your foundation with creative flair. Suggested listening: soft rock, soft pop or soft jazz, avoiding hard rock, hard pop, hard jazz or any music that causes your heart to race. Stay calm. If possible, outsource this task to a younger, more naïve do-gooder, sibling or friend with a high threshold for glue-related burns and pain and one who can maintain focus for up to eighteen hours at a time or until this part of the project is complete.

4.) Set the mood with candle light. Extinguish paper fire that ensues. It will look like garbage, but don’t despair.

5.) Go on a beer and pizza mission.

6.) Call your boyfriend and tell him you won’t be coming home tonight.

7.) With the major construction now complete, it’s time to paint. Go nuts.

8.) While paint is drying, draw the silhouettes of your main characters onto construction paper. Quickly realize that you cannot draw people or animals or trees. Rely on Google to inspire you and try again. Nailed it. Now carefully cut them out.

9.) Place your characters and cut-outs using glue and plasticine. Force delicate pre-made paper-cutting illustration (square peg) to work within your spiky cardboard trap (round hole).

***NOTE: At this point, your diorama will likely resemble a pile of garbage. Don’t worry about it. Magic is about to happen.

10.) Set up a camera on a tripod, frame your composition and set the exposure to allow for a shutter speed of between 10 and 20 seconds.

11.) Turn off the lights so it is completely dark in the studio/bathroom.

12.) Pull out your iPhones and pen light. Proceed to shoot 300 or so long exposures of the diorama as you creatively “paint with light” using your handy hand-held lights.

13.) Upload your images, pick your favorite shot and publish that little beauty.

14.) Accept Pulitzer.